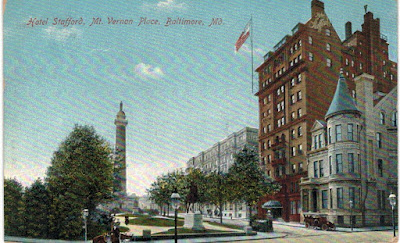

The hotel was

completed and opened by July 1, 1894. The front and sides of this fireproof

hotel were Pompeiian bricks and brownstone in the Romanesque style. The main

entrance led to a tilled hallway decorated in Romanesque designs. Soft

monotints of the wall and ceilings were relieved with friezes and borders in

conventional patterns flecked with gold. To the right of the hallway was the

ladies' reception room, entered by a separate street entrance, and decorated in

the Louis XVI style. Adjoining is room was the main office, private office, and

elevator entrance.

On the left of the

hallway was the main dining room carpeted in crimson, and with oak furnishings.

The table appointments were all marked with the Stafford coat of arms, and the

central panel in the front window of the dining room was formed of the coat of

arms in colored glass. All the brass electric light brackets and chandeliers

bore reproductions of the Stafford arms. To the rear of the dining room was the

café, smoking and lounging rooms, bar, barber shop, and coatroom.

There were also iron

and stone stairways encircling the central rotunda of the of the building,

which was lighted through a skylight. Two passenger elevators and a freight

elevator also gave access to the upper floors. There was also a newsstand located in the rotunda.

The second floor contained the ladies' parlor and drawing room facing

Washington Place, with a writing room adjoining. A café was also on this for

ladies traveling unattended and for permanent guests who did not care to go to

the public dining room. White and gold decorations and furniture gave this room

an attractive appearance. Private dining rooms, adjoining a reception room for

their occupants, occupied the back of the second floor.

On the upper floors

were 140 bedrooms and 30 private parlors in suites. Each floor had connecting

rooms for the convenience of families and parties occupying them. Eighty

bathrooms were scattered among the suites. The hotel also featured a bridal

chamber which was finished in delicate shades of carpet and hangings, with

ivory and gold furniture to correspond. The other chambers and parlors were

finished with solid colored carpets and furniture of oak, birch and maple of

handsome design. The hallways throughout the hotel were carpeted in crimson to

great effect. And each room was connected by telephone with the hotel office

and was lighted with incandescent lamps.

The twelfth floor

contained a trunk room for guests’ baggage.

Decorating of the

original hotel was done by Emmart & Quarterly, with J.W. Putts and Company

providing the crockery and Reed & Barton providing the silverware.

By 1906 it was time to update the hotel, which though modern for its time when

built, was in need of updating foe the 20th Century. Charles E. Cassell &

Son were selected as the architects for the improvements and Edward Brady &

Son was the contractor doing the work on the hotel. With a budget of $50,000,

the remodeling included new furniture in every bedroom, as well as the

reception rooms, dining room, lobby, rotunda and other apartments. The major improvements

were however to be on the first floor and basement of the hotel.

Partitions were

installed on each side of the entrance corridor, dividing the dining room. The

ladies’ reception room and office were removed. The dining room was widened as

far back as the rotunda and all of the space on the other side of the dining

room was be occupied as a lobby or lounging room. The dining room was divided

off by a French beveled plate glass partition with glass doors. The glass

partition was trimmed with bronze and had a marble base. French plate glass

mirrors, resting on marble bases, were hung on all the walls of the dining room

and the large marble columns which were on the south side of the dining room,

and had been decorated with numerous electric wall lights were removed. The woodwork if the dining room was of a Verde antique

bronze finish. Candelabra with colored shades were placed on the tables and

projecting from the ceiling were electric lights. The lights were covered with

the coat of arms of the hotel and large prism glass globes.

Lights similar to those in the dining room were installed in the lobby. Sheraton

style furniture was ordered for the hotel, the first-floor chairs and couches

were of mahogany and antique woodwork, being finished in crimson leather, the

larger pieces bearing the crest of the hotel. The A.B. & E.L. Shaw Company

of Boston supplied the lobby furniture. The crest was also hung crest now hangs on the walls

of the entrance corridor. This crest represented the original coat of arms of

the Duke of Stafford who was a relative of Dr. Moale who established the hotel.

The partitions at the rear of the rotunda which had formed the barber shop,

toilet, package and storage rooms were removed and the space devoted to the

office, telegraph and telephone booths, and check room. To the north of the

lobby was now the ladies retiring room which contained a dresser, mirror and

washstand. The roof of this retiring room was of glass and from it suspended

droplights. The hotel office was now situated in the space formerly occupied as

the public toilet and cloak room, the news stand, and barber shop. Mont Blanc

marble, with a beautiful red vein running through it, divided the office.

Opposite the office was now the telegraph station and news stand. The cafe and

bar were redecorated with bright colors on the walls, and the woodwork was re-polished.

A marble stairway was installed to connect the basement and first floor.

On

the south side of the basement, directly below the dining room a grill room was

created. Entrance to the grillroom was gained by a corridor which was reached

by the new marble stairway leading from the office above. The grill room

featured a floor of mosaic and the woodwork finished in quartered fumed oak,

the panels and the ceiling to correspond. The caps of the marble columns were

solid gilt with gilded ornaments at the intersections of the main ribs. The chairs of the grill were of

mission style. The electric fixtures were

of hammered brass. Reminiscing in 1944, James

P.A. O'Connor, first manager of the bar, who worked at the hotel from 1894

to 1911, described the original bar as thimble sized with the proverbial black

leather upholstered furniture.

On the north side of the corridor in the basement a

men's toilet, barber shop and bootblacks’ rooms were created. The floor of both

the basement and the first floor were of white marble and mosaic with colored

borders which kept with the architecture of the hotel.

A number of changes

were made on the fourth, fifth, and sixth floors. These bedrooms were enlarged

with the removal of partitions. New mahogany furniture was ordered for each

room, as well and other rooms of the hotel, and new satin finish brass beds

were purchased for the 150 bedrooms.

The entire hotel was

re-carpeted with Persian rugs, every room and corridor repapered and repainted,

new draperies of silk tapestry hung, and a new range installed in the kitchen.

With renovations

complete, the first floor which had previously seemed crowded by the office and

the ladies’ reception room in the front was now roomy and up to date.

On June 28, 1908

Princess Lwoff-Parlaghay arrived at the Stafford Hotel taking the entire second

floor of 13 rooms which had been reserved for her, staying until the next

Thursday.

In 1911 dining room of the hotel was again

redecorated, painters and decorators making the white room a veritable bower of

gilt and white.

By 1918 the hotel

boasts 132 rooms and a staff of 93 people, to include: 9 chambermaids (2 in

linen room), 3 day scrub women, 3 night scrub women, 2 housemen, 2 passenger

elevator men, 2 freight elevator men, 1 painter, 5 bellboys, 2 parlor maids, 11

waiters, 1 waitress, 1 busboy, 2 captains, 1 porter, 1 yardman, 1 fireman, 1

watchman, 15 kitchen help, and 11 pantry help.

In 1931 the hotel was

taken over by the Stafford Hotel Apartment Company which ran the hotel until at

least 1960. That year, with the new ownership, extensive alterations were

commenced on the hotel, with the entire hotel being repainted and refurbished,

and the entire lobby and dining room were greatly enlarged and completely

redecorated. At least a portion of the original hotel furnishing we disposed of

at this time.

Main Lobby

circa 1946

The hotel was again

remodeled and redecorated in 1934, with the bar/grill being rechristened the

Hunt Room by Manager Morton A. Grant. Only the old mahogany bar top remained of

the former furnishings. The room was now bright and snappy with pastel shades

and mirror finishes. The bar, which accounted for 40 to 50 percent of the

profits of the hotel, was formerly a dreary wood paneled bar. It opened

September 6, 1934 as the Hunt Room Cocktail Lounge, S. Dickson Wright manager

at the time. At it's opening it was called a "classic mirror bar in our

new Grecian Hunt Room." This bar remained through at least 1948. The

remodeled dining room also opened that day.

Original Grecian Hunt Room

The hotel was again

redecorated in 1935 and underwent another refurbishing in 1936. The later

refurbishment resulted in the lobby being decorated in pink and silver. One of

the famous guests at this time was F. Scott Fitzgerald who checked in on

December 26, 1936 into room 409 and ran up a $22.35 bar and restaurant bill.

Hunt Room Cocktail Lounge

By 1944, few of the

original furnishings remained, a few coffee pots, several silver trays, and

several old prints of hunt scenes that once adorned the bar. However, brought

back to sight about that time was the original marble mosaic floor in the foyer

which had been covered by carpets for many years. But gone was the plate glass

wall separating the dining room from the foyer. That wall was removed when the

dining room was moved to the second floor. Gone also was the tiny circular

elevator that operated in the rear corner of the foyer. This disappeared when a

new elevator was placed in the well made by a circular staircase which was once

the pride of the hotel especially because of its wrought iron railing. Still remaining

at this time was the marble and tile lined cellar. Also still in operation was

the boiler room under the bed of Washington Place with a manhole though which

coal was fed to the boiler room. As mentioned above, tiny bar with its with

black leather covered furniture, and adjoining barbershop of thimble size, had

all disappeared and the entire space given over to a large modern lounge.

Typical Bedroom

In 1946 the 52-year-old

marquee was removed, an old iron canopy which was held in place by huge chains

and reached from the building to the curb line.

By 1960 the bar had

been rechristened the Coach Room Bar. In 1962 the lobby was remodeled,

enlarged, repainted and new lighting was installed. At this time the dining

room and the banquet rooms were repainted, and new lighting and new wall to

wall carpets installed. The following year the lobby corridors were remodeled

was well as the hotel rooms, the later being enlarged and redecorated. They

also converted the first floor Mount Vernon Room into a dining room, which was enlarged,

redesigned, and relighted.

The hotel finally

closed on January 15, 1973 after nearly 79 years in business, being taken over

by the Facilities Management Corporation. Later that month the hotel was

"gutted." Cleaned out in a few hours in what was described in the

newspapers of the days as a "loot riot" and "ten story flea

market." Solid brass chandeliers sold for $45, bathtubs for $10, room

numbers for $2. Other items included marble topped night stands, framed

pictures, lamps and Sheraton style dressers with inlaid wood décor and glass

tops.

Today the building

still stands, now used for apartments, little if any of the interior design

features remaining.

No comments:

Post a Comment